The male of Erythiagrion alidae, and the first mature adult of the species ever photographed. Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo Conservation Area, Peru; 2 April 2023. Photo Maximilian Christie

October 2025 Species of the Month

Erythiagrion alidae

DSA’s species of the month for October is Erythiagrion alidae, a Peruvian damselfly belonging to the family Coenagrionidae (colloquially known as pond damselflies). E. alidae (as well as the genus Erythiagrion) was described in 2025 by Max Christie, Emmy Medina-Espinoza, and Tim Faasen. According to their paper, this species is 32-36 mm in length, and inhabits flooded blackwater forests with strangler fig trees. Read on to hear Max’s exciting account of the discovery and description of Erythiagrion alidae.

A Peruvian Adventure

Each dragon has a legend, every damsel has a tale to tell. Odonata’s endless forms most beautiful boast greater riches than any Roman hoard or pharaoh’s tomb, so glamorous are these jewels of Arthropoda.

I’ve had the great privilege of describing one such jewel, whose tale I’m telling you today. Erythiagrion alidae is named after two important figures. Erythiagrion references Erythia, one of the Hesperides sisters who guard the sacred boughs of the golden apple tree. The Hesperides are nymphs of the golden light of sunset in Greek mythology, and so the name is a nod to the yellow and red tones of this damsel. The species epithet, meanwhile, is in honour of my wonderful mother Alida, whose love and support gave this project its wings.

The story begins in April 2023 when, aged fifteen, I conducted a survey of the damselflies of Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo Reserve, nestled in Peru’s Amazon jungle. I netted and photographed around 40 species of Zygoptera in two weeks, across habitats including black and white water rivers, terra firme, higher and lower restinga, oxbow lakes, and igapó forest. One day, when sampling in flooded tahuampa (blackwater) forest, E. alidae and I crossed paths by chance.

The first time E. alidae regarded me, with wonder etched upon its impish face, I think it was the eyes that most bewitched me. The male’s eye glistens like an emerald sphere with a black, earthen crust encroaching from above. The sort of lustrous thing you’d find down a mine in the depths of Tolkien’s imagination.

The male of Erythiagrion alidae, and the first mature adult of the species ever photographed. Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo Conservation Area, Peru; 2 April 2023. Photo Maximilian Christie

Below these eyes, E. alidae sports a rounded frons. This gives the visage a distinctly friendly tone and so, despite the hues of yellow and charcoal black, there is nothing wasp-like in those features whatsoever. Yellow and black stripes adorn this damsel for the most part, save for the tip of the abdomen, which seems to have been dipped in scarlet flames.

When I sent my photos of this Odonate to Tim Faasen, a Dutch odonatologist and my mentor, he confirmed that this was the first adult of three teneral specimens he had collected in previous years. What’s more, this damsel belonged to a novel species from a genus new to science. Needless to say I was thrilled by such a revelation.

In April 2024, I returned to Peru with authorization to collect specimens of this undescribed species. I embarked on the expedition with the knowledge that finding a particular species twice can prove fiendishly tricky. In spite of this, Hersog Chavez Yuyarima (my guide) and I found males of E. alidae on our first day in the field, and the first females two days later.

The female of Erythiagrion alidae. Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo Conservation Area, Peru; 8 April 2024. Photo Maximilian Christie

All these forest wisps were spied within the sprawling roots of strangler fig trees (Ficus sp.). In fact, all fifteen specimens of E. alidae that I collected were found within the roots of the same plant. To have conspecific damselfly populations aggregating around particular trees with such fidelity is distinctly unordinary. The population I observed likely comprised fairly young adults, as only a few unsuccessful attempts from males to initiate copula were witnessed.

It seems probable that the strangler fig plays an important role in the survival or reproduction of E. alidae. Teneral specimens have been recorded as early as February, and their flight season likely extends to at least the end of April. The tahuampa and igapó forests that these damselflies inhabit flood seasonally with black water, and are dry roughly between the months of June and October. E. alidae is almost certainly not on the wing during this period, so the question is: how does it survive the dry months of the year? One theory is that water retained between the roots of the strangler fig maintains a suitable aquatic environment for larvae. Alternatively, E. alidae could wait out the dry season as an egg, or even as an aestivating adult. These latter hypotheses would require highly accelerated larval development.

Looking for Erythiagrion alidae in the roots of a strangler fig tree. Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo Conservation Area, Peru; 8 April 2024. Photo Hersog Chavez Yuyarima

As my time in Peru drew to an end, I made provisional photographs of E. alidae under the microscope at the Museo de Historia Natural in Lima with the help of Emmy Medina-Espinoza. Then, in the summer of 2024, I wrestled with the task of describing a species new to science.

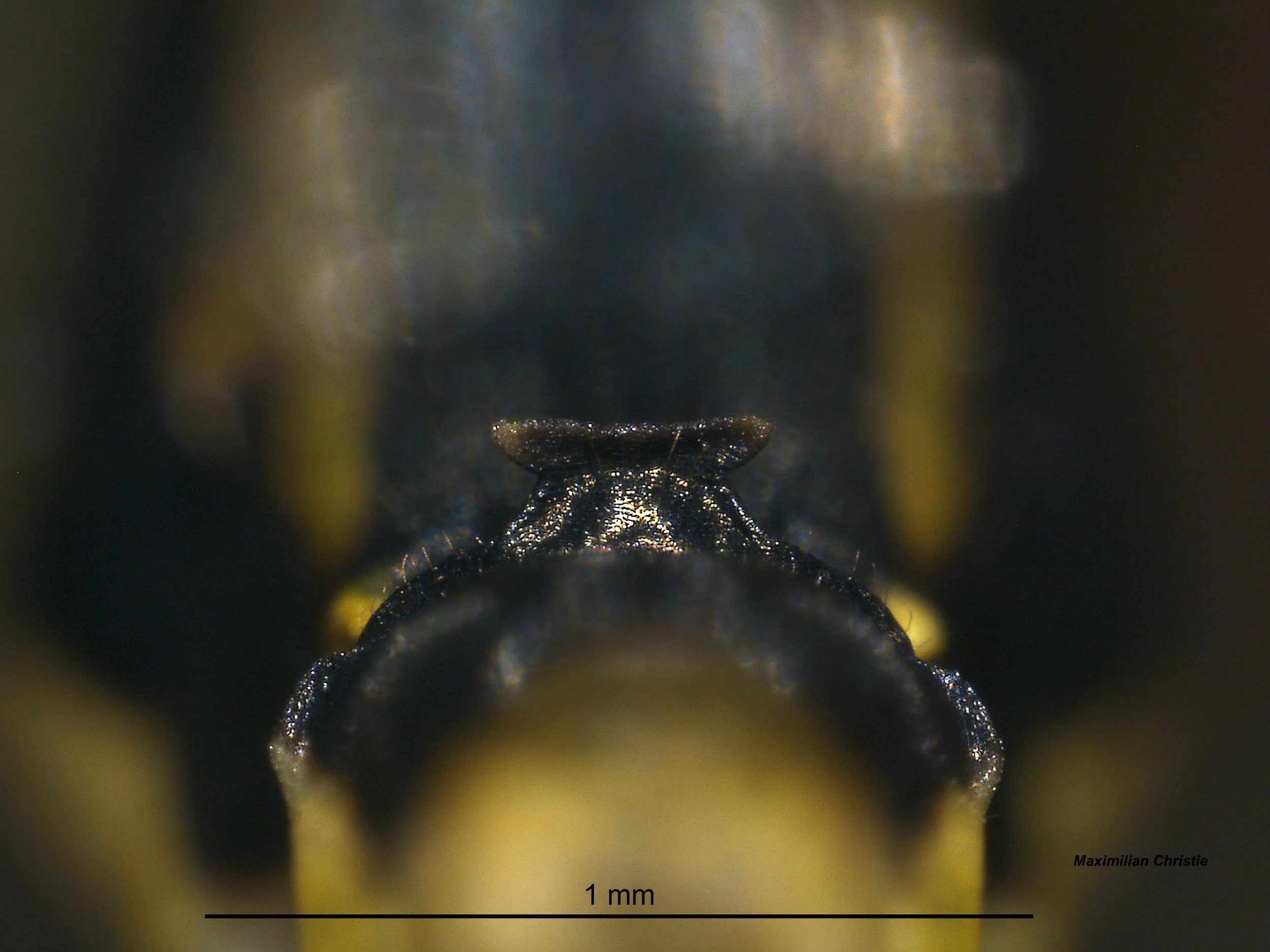

Considering each intricacy of my specimens, then constructing them with words was almost meditative. Take, for instance, the genital ligula of E. alidae, which bears two pairs of lateral processes. Looking up at the proximal pair they appear thorn-like, with finely serrated edges and pricking spines at their tips. The distal pair, meanwhile, are broad and blunt in a stoic sort of way. Viewed laterally, each calls to mind the dorsal fin of a Silky Shark, just breaching the ocean’s surface. Continuing further down the abdomen, the male cercus (which is shorter than the paraproct) resembles a leaf in autumn fire, and the female cerci could be likened to stubby, blood-red fangs. In the male hindwing there is a black wingspot caudally bordering the pterostigma … rather wonderful, don’t you think?

A close-up image of the male posterior prothoracic lobe process, taken at the Museum of Natural History in Lima. The structure resembles a grand anvil … or perhaps a banana on a pedestal (depending on how you look at it!) Erythiagrion alidae; Museo de Historia Natural, Lima, Peru; 15 April 2024. Photo Maximilian Christie

In June 2025, almost a year after I began work on the specimens, the paper describing Erythiagrion and its type species was published in the International Journal of Odonatology, complete with other sections written by my co-authors, Tim and Emmy, and myself. Revising each new draft of the species description based on the insightful comments of Tim (and later our peer reviewers) was extremely fulfilling. Thanks to E. alidae, my life has been full of damselflies these past few years. I can only hope my next few are the same.

Max Christie is a high school student living in the United Kingdom. His passion for damselflies began on the banks of a stream in a Tuscan woodland. You can contact him at mcf.christie@gmail.com